First Posted on September 28, 2012 by Solomon Appiah

What is Africa?

Africa is the world's second largest and second most-populous continent next to Asia in both categories. The continent is made up of 54 sovereign states and some territories. The continent is so vast that one can fit the United States, China, India, United Kingdom, Germany, France within the continent and still have plenty more room.

The map is taken from a CNN story titled, “What's the real size of Africa? How Western states used maps to downplay size of continent”.[1]

This continent has been subject to different competing narratives majority originating from Western media outlets and misleading in nature.

Misleading Narrative

In the May 13, 2000 print edition of The Economist Magazine, the cover page had a map of Africa superimposed on a black background with the title “The Hopeless continent”. In a May 11, 2000 article entitled “Hopeless Africa”, the Economist explained why Africa is hopeless. It alleged that for reasons buried in African cultures, Africans seem especially prone to brutality, despotism and corruption (The Economist, 2000). In the Economist article dated May 11, 2000 and titled ‘The heart of the matter’, the magazine explains that “Africa’s biggest problems stem from its present leaders. But they were created by African society and history”. The article succumbed to stereotyping 54 counties as if they were one country with a collective history. Fast-forward to 2018, it would seem the continent has proved The Economist wrong. More on that in the last section of this article.

Why Africa Is the Way It Is

To rightly and justly evaluate Africa, one has to consider not only what they see, i.e. the EFFECT or symptoms but also the CAUSE(s). To understand this continent, one must consider its internal governmental systems and how they influence the governance of this continent and also the external global governance systems and how they impact on the continent and its internal happenings. External factors that have contributed to the current political, economic and cultural landscape of Africa can be subdivided into historical and current.

The succeeding sessions of this piece attempts to tease out some reasons why the continent is in the shape it is in currently. Then the concluding section will focus on how blessed Africa is and the current opportunities within the continent.

Before I proceed, here’s a disclaimer: This piece is by no means an attempt to justify poor governance or corruption by Africans and their leaders. The author admits that quite a number of African countries suffer from corruption and poor governance and these challenges need to be confronted head-on by African themselves.

Consequences of the European Scramble

A 2011 study by Stelios Michalopoulos and Elias Papaioannou revealed that:

Civil war intensity is much higher in the historical homeland of ethnic groups that have been partitioned by national borders”. The study adds that, “regional development is significantly lower in areas of ethnic groups that have been affected by the artificial border design”.

In the 1800s, European powers carved up Africa thereby creating artificial borders. This is what is known as the scramble for Africa.

The "Scramble for Africa" is the invasion, occupation, colonization and annexation of African territory by European powers during the period of New Imperialism, between 1881 and 1914. It is also called the Partition of Africa and the Conquest of Africa

Research proves that Africa’s present condition is in part a consequence of overt and covert actions of European powers such as Great Britain, France, Portugal, Germany and Belgium. These nations annexed sovereign Africa states (LAND), depleted them of much needed human resource (LABOUR) through the slave trade, partitioned the continent amongst themselves through colonization, and took over their natural resources (CAPITAL) and used it as inputs for their industrialization.

Land, Labour and Capital are the traditional factors of production. These nations developed by impoverishing others. Such actions have consequences. The following section summarizes what happened during the European expansion within Africa and other areas. The next section explains what transpired during the European expansion and how this affected Africa.

European Expansion Since 1763

The global expansion of Western Europe between the 1760s and the 1870s differed in several important ways from the expansionism and colonialism of previous centuries…Instead of being primarily buyers of colonial products (and frequently under strain to offer sufficient salable goods to balance the exchange), as in the past, the industrializing nations increasingly became sellers in search of markets for the growing volume of their machine-produced goods…Before the impact of the Industrial Revolution, European activities in the rest of the world were largely confined to:

(1) occupying areas that supplied precious metals, slaves, and tropical products then in large demand

(2) establishing white-settler colonies along the coast of North America

(3) setting up trading posts and forts and applying superior military strength to achieve the transfer to European merchants of as much existing world trade as was feasible.

The adaptation of the non-industrialized parts of the world to become more profitable adjuncts of the industrializing nations embraced, among other things:

(1) overhaul of existing land and property arrangements, including the introduction of private property in lands where it did not previously exist, as well as the expropriation of land for use by white settlers or for plantation agriculture

(2) creation of a labour supply for commercial agriculture and mining by means of direct forced labour and indirect measures aimed at generating a body of wage-seeking labourers

(3) spread of the use of money and exchange of commodities by imposing money payments for taxes and land rent and by inducing a decline of home industry; and

(4) where the precolonial society already had a developed industry, curtailment of production and exports by native producers.

The classic illustration of this last policy is found in India. For centuries India had been an exporter of cotton goods, to such an extent that Great Britain for a long period imposed stiff tariff duties to protect its domestic manufacturers from Indian competition. Yet, by the middle of the 19th century, India was receiving one-fourth of all British exports of cotton piece goods and had lost its own export markets.

The changing nature of the relations between centres of empire and their colonies, under the impact of the unfolding Industrial Revolution, was also reflected in new trends in colonial acquisitions. While in preceding centuries colonies, trading posts, and settlements were in the main, except for South America, located along the coastline or on smaller islands, the expansions of the late 18th century and especially of the 19th century were distinguished by the spread of the colonizing powers, or of their emigrants, into the interior of continents. Such continental extensions, in general, took one of two forms, or some combination of the two:

(1) the removal of the indigenous peoples by killing them off or forcing them into specially reserved areas, thus providing room for settlers from western Europe who then developed the agriculture and industry of these lands under the social system imported from the mother countries, or

(2) the conquest of the indigenous peoples and the transformation of their existing societies to suit the changing needs of the more powerful militarily and technically advanced nations.[2]

There is no way the abovementioned activities will not leave a scar on the victims. Manifestations of these scars include the many conflicts that Africa of yesteryears faced.

The Time Factor

The first sub-Saharan African country to gain independence from colonialism is Ghana. It attained Independence in 1957. Ghana is therefore 61 years old. The last country to be rid of the vestiges of colonialism on the African continent is South Africa which wrested freedom from the shackles of Apartheid in 1994 i.e. only 24 years ago. African countries have only been free to rule themselves for 24 – 61 years. Prior to this time, they were subjugated by foreign powers. Compare Ghana the oldest independent sub-Saharan nation with for example the USA. The USA gained independence from Great Britain in 1783 i.e. 235 years ago. The USA has had centuries head start—in building stable state institutions and solidifying its democracy.

It would be thus unfair for anyone to expect Ghana or South Africa to be on the same plane as the USA when it comes to democratic governance or national development. Building solid government, governance and leadership systems takes time and this time can be extended even more when external powers keep interfering in the governance of African countries.

Foreign Interferences

Foreign interferences in the governance of African nations in the form of coup d’états impede development. A coup d’état is a strike against the state usually entailing military intervention. For decades Western powers have been orchestrating coup d’états in many countries in Africa and around the world. Let’s first consider one carried out outside Africa and then the first carried out in sub-Saharan Africa.

1953 Iran Coup d’état

The 1953 Iranian coup d'état, known in Iran as the 28 Mordad coup d'état was the overthrow of the democratically elected Prime Minister Mohammad Mosaddegh in favour of strengthening the monarchical rule of Mohammad Reza Pahlavi on 19 August 1953, orchestrated by the United Kingdom (under the name "Operation Boot") and the United States (under the name TPAJAX Project or "Operation Ajax").[3]

Mossadegh had sought to audit the documents of the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company (AIOC), a British corporation (now part of BP) and to limit the company's control over Iranian petroleum reserves. Upon the refusal of the AIOC to co-operate with the Iranian government, the parliament (Majlis) voted to nationalize Iran's oil industry and to expel foreign corporate representatives from the country. After this vote, Britain instigated a worldwide boycott of Iranian oil to pressure Iran economically. Initially, Britain mobilized its military to seize control of the British-built Abadan oil refinery, then the world's largest, but Prime Minister Clement Attlee opted instead to tighten the economic boycott[14] while using Iranian agents to undermine Mosaddegh's government. Winston Churchill and the Eisenhower administration decided to overthrow Iran's government, though the predecessor Truman administration had opposed a coup, fearing the precedent that CIA involvement would set. Classified documents show that British intelligence officials played a pivotal role in initiating and planning the coup, and that the AIOC contributed $25,000 towards the expense of bribing officials. In August 2013, 60 years after, the American Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) admitted that it was in charge of both the planning and the execution of the coup, including the bribing of Iranian politicians, security and army high-ranking officials, as well as pro-coup propaganda. The CIA is quoted acknowledging the coup was carried out "under CIA direction" and "as an act of U.S. foreign policy, conceived and approved at the highest levels of government".[4]

1966 Ghana Coup d’état

According to declassified National Security Council (NSC) and Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) documents, the first successful coup d’état in Ghana in 1966 was CIA assisted and sanctioned by the administration of Lyndon B. Johnson (Lee, 2001; Gebe, 2008; David & Majeski, 2009, p.46-47).

The coup d’états took place on February 24 1966 and by March 4 1966, the coup makers received the international recognition from America and the UK. The new unconstitutional government overturned the policies of the ousted government which included free education and healthcare in favor of pro-western policies.

Initially the Coup makers i.e. the new government were renounced by some African leaders when they went to their first OAU meeting but having received the blessing of the U.S. and Britain, they soon had to be accepted by the OAU.

This precedence of unconstitutionally overthrowing a government with the blessing of strong allies in the West set a bad precedence for the fledgling African democracies.

Still on foreign interferences and the impact on African countries, Charles Taylor, the former President of Liberia was instrumental in destabilizing his nation and other nations like Sierra Leone through civil wars. The wars brought to the fore the selling of what we now call blood diamonds. At his trial, he confessed working with the CIA who initially denied the allegations. Later the Pentagon admitted that this was true but refused to mention the details of the association with Mr. Taylor.

Foreign interferences by way of coup d’états sponsored by the West have played a crucial role in retrogressing development in Sub-Saharan Africa.

Corruption

Are African politicasters corrupt? Yes! But is this the kind of corruption that is impeding development? Nope.

Honest Accounts Report

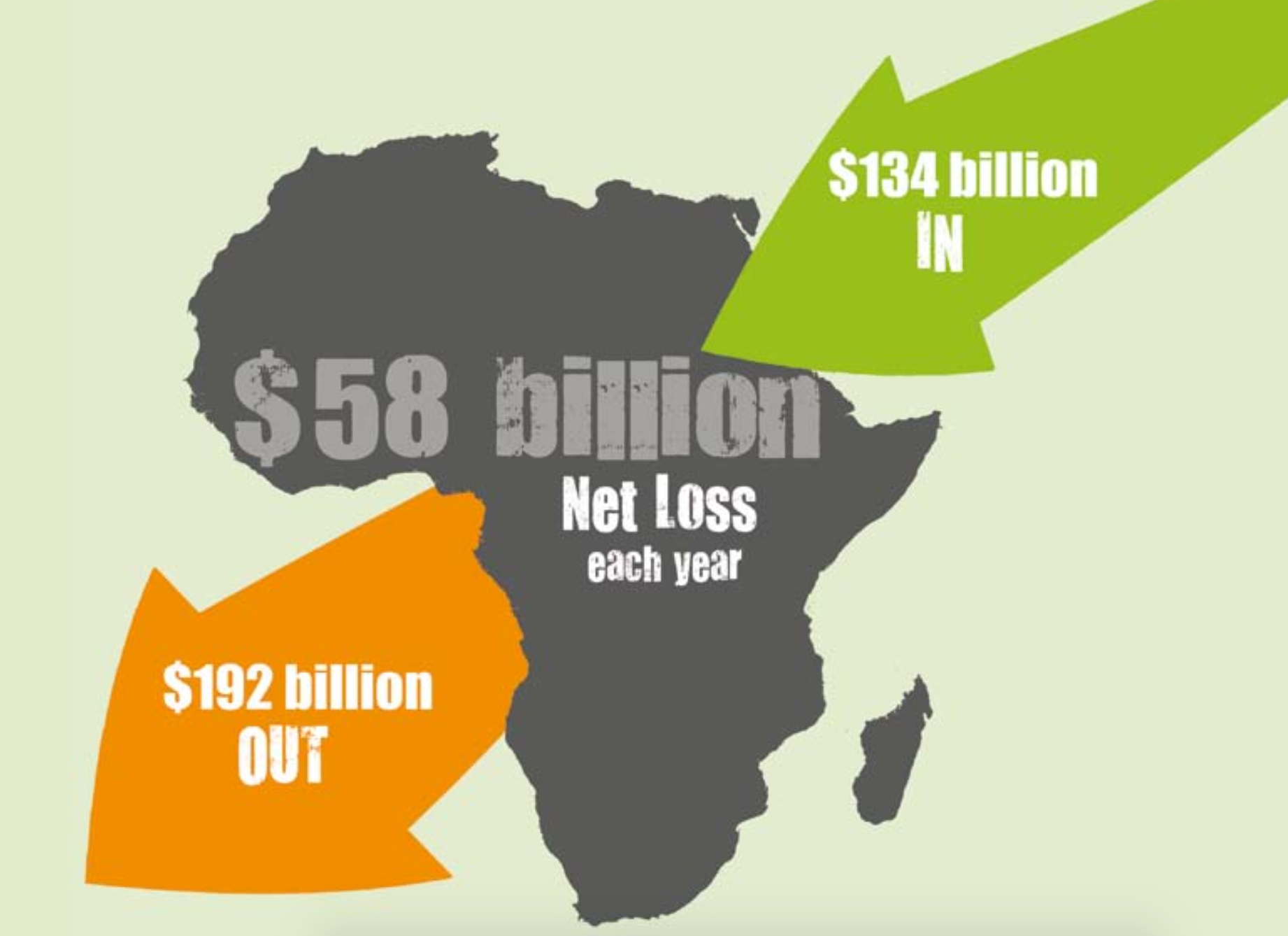

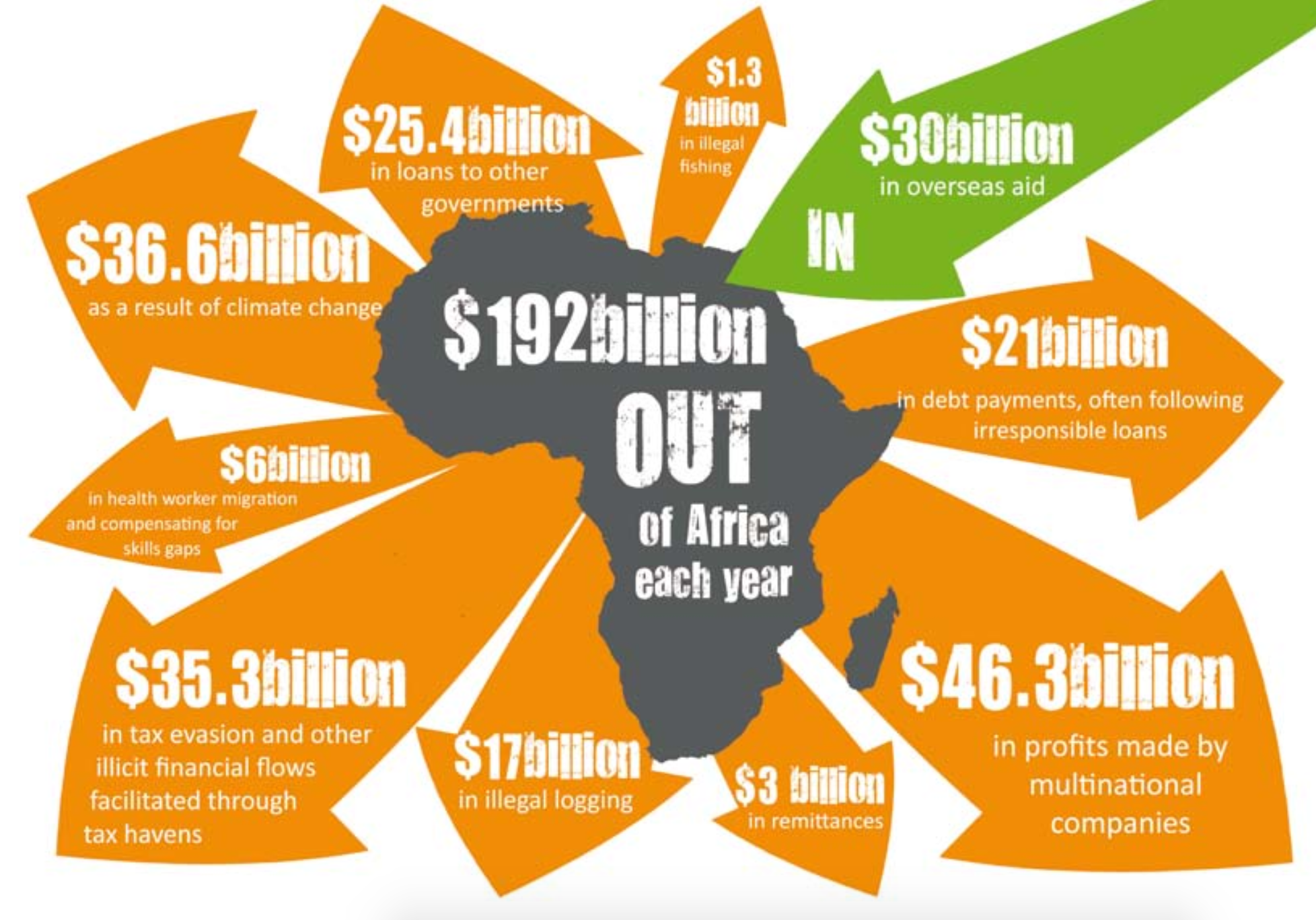

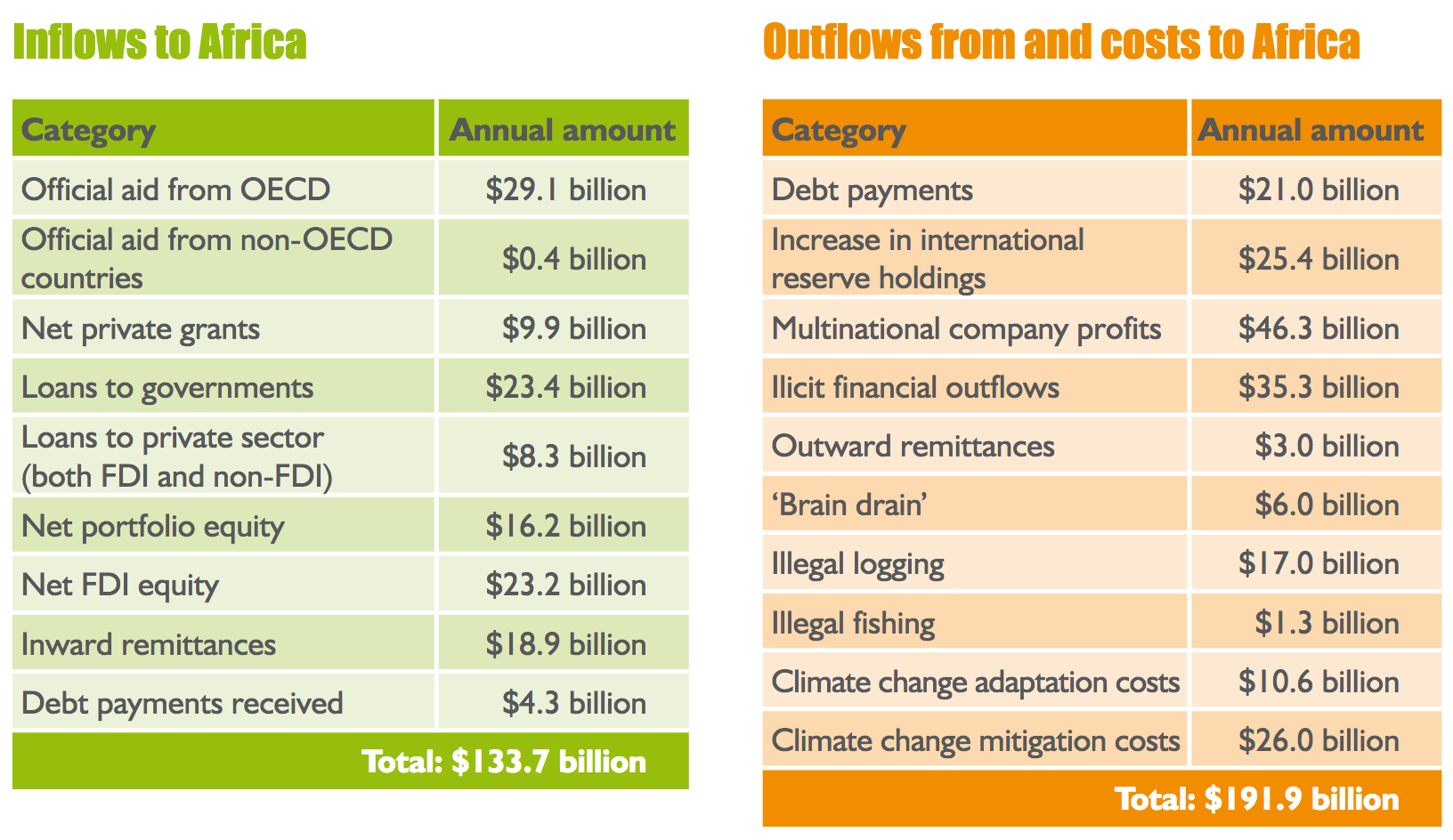

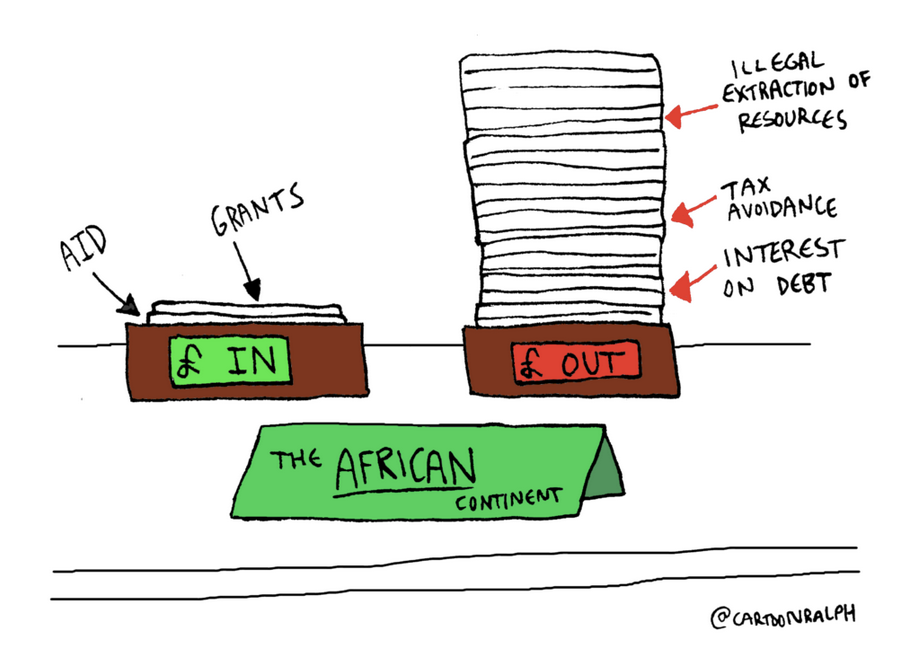

In a report “Honest Accounts? The true story of Africa’s billion-dollar losses”, published by Health Poverty Action and co-authored by a range of other civil society organizations, the inflows to and outflows from Africa are contrasted. The continent records an annual net loss of US$ 58.2 billion mostly flowing into the pockets of Western governments or transnational corporations, according to the report. Overseas Developing Aid (ODA) coming into the continent is about US$30 billion but the continent loses annually US$192 billion. Africa is thus a net creditor to the world.

In financial terms, the report illustrates the loss to Africa as follows:[5]

- US$46.3 billion in profits made by multinational companies

- US$21 billion in debt payments, often following irresponsible loans

- US$35.3 billion in illicit financial flows facilitated by the global network of tax havens

- US$23.4 billion in foreign currency reserves given as loans to other governments

- US$17 billion in illegal logging

- US$1.3 billion in illegal fishing

- US$6 billion as a result of the migration of skilled workers from Africa

- US$10.6 billion to adapt to the effects of climate change that it did not cause

- US$26 billion to promote low carbon economic growth

[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=E5hdcfFyahM]

Global Financial Integrity Report

Another report by Global Financial Integrity found that even after you account for all types of financial flows (both legitimate and illegitimate)—including investment, remittances, debt forgiveness, and natural resource exports—Africa is a net creditor to the world. GFI estimates that in 2013, US$1.1 trillion left developing countries in illicit financial outflows. This estimate is regarded as highly conservative, as it does not pick up movements of bulk cash, the mispricing of services, or many types of money laundering. Measured against the level of trade, Sub-Saharan Africa ranked highest in illicit outflows, ranging from 5.3 percent to 9.9 percent of total trade in 2014.[6]

UNECA Report

Another report titled ‘Illicit Financial Flow Report of the High Level Panel

on Illicit Financial Flows from Africa’ commissioned by the AU/ECA Conference of Ministers of Finance, Planning and Economic Development makes an astonishing claim that:

Over the last 50 years, Africa is estimated to have lost in excess of $1 trillion in illicit financial flows (IFFs[7]) (Kar and Cartwright-Smith 2010; Kar and Leblanc 2013). This sum is roughly equivalent to all of the official development assistance received by Africa during the same timeframe. Currently, Africa is estimated to be losing more than $50 billion annually in IFFs. But these estimates may well fall short of reality because accurate data do not exist for all African countries, and these estimates often exclude some forms of IFFs that by nature are secret and cannot be properly estimated, such as proceeds of bribery and trafficking of drugs, people and firearms. The amount lost annually by Africa through IFFs is therefore likely to exceed $50 billion by a significant amount.

With Africa being a net creditor to the nations—losing more funds than what is brought into the continent, how is it supposed to retain any money for development related activities?

This argument is seldom made. Rather her countries are castigated for being corrupt and yet the greater corruption lies with Western governments and the transnational corporations that take out more than they put within the continent.

Africa the Land of Opportunities

All of the above-mentioned challenges notwithstanding, Sub-Saharan African states have not done pretty badly when one considers the odds stacked against them.

Here’s a fact about Africa “…it took [the] UK 155 years to double its GDP during the industrial revolution and Africa has achieved the same in the last twelve, it is imperative to capitalize on growth for real transformation”.[8]

When we consider such a fact, it’s easy to see why Africa is hopeful and not as hopeless as a segment of the media depicts it to be sometimes so long as the continent’s current leadership get their policies right. This statement was taken from a speech by Mr. Carlos Lopes former UN Under-Secretary-General and Executive Secretary of ECA at the Third Annual Conference on Climate Change and Development in Africa (CCDA-III).

This does not negate the fact that a lot more work remains to be done on the continent to reduce income and wealth disparities, and promote better governance in the public, private and NGO sectors. The continent knows this and the African Union is working tirelessly to this end.

The UN magazine, Africa Renewal carried a story titled “African economies capture world attention” with a subtitle “But huge challenges still lie ahead”. This article outlines some of the promising economic indicators that have made Africa a favourable destination for more and more investors. The article explains that since The Economist article came out 12 years ago, “Africa’s trade with the rest of the world has increased by more than 200 per cent, annual inflation has averaged only 8 per cent and foreign debt has decreased by 25 per cent. Foreign direct investment (FDI) grew by 27 per cent in 2011 alone”.

But what are the factors behind these positive indicators? The article cites “an end to many armed conflicts, abundant natural resources and economic reforms that have promoted a better business climate”.

In 2018, many of the fastest growing economies in the world will be from Africa as per World Bank. The fastest growth is slated to be Ghana’s. According to the World Bank’s Africa’s Pulse:

Economic growth in Sub-Saharan Africa is estimated to have picked up to 2.6 percent in 2017 from 1.5 percent in 2016. This upswing reflected,

…on the supply side:

- rising oil and metals production, encouraged by recovering commodity prices, and

- improving agricultural conditions following droughts.

On the demand side:

- growth was supported by a rebound in consumer spending as inflation moderated, and

- a recovery in fixed investment as economic activity picked up among oil and metals exporters.

Recent data point to a moderate strengthening of growth in the region. Growth is projected to pick up to 3.1 percent in 2018, slightly below what was forecasted in the October issue of Africa’s Pulse, and to firm to an average of 3.6 percent in 2019–20, reflecting a gradual pick-up in growth in Nigeria, South Africa, and Angola—the region’s largest economies. These forecasts are predicated on the expectations that oil and metals prices will remain stable, robust expansion in global trade will continue, external financial market conditions will remain supportive, and governments in the region will implement reforms to tackle macroeconomic imbalances and boost investment.

The external environment facing Sub-Saharan Africa remains favorable. Global growth is estimated to have reached a stronger than expected 3 percent in 2017, up from a post-crisis low of 2.4 percent in 2016. This improvement reflected an investment-led pick-up in advanced economies and a growth acceleration in EMDEs, where activity in commodity exporters rebounded. Incoming data point to the continuation of strong growth in 2018. The global composite Purchasing Managers’ Index (PMI) rose to 54.8 in February, its highest reading since mid-2014.

The rise of the African consumer: A report from McKinsey’s Africa Consumer Insights Center notes that the following are going in Africa’s favor:

Explosive Population Growth

Africa has the world’s fastest-growing population and is projected to account for more than 40 percent of global population growth to 2030, according to the United Nations. Thanks to declining fertility rates, it is the working-age population that will have the highest growth rate. (In fact, by 2040, Africa’s working-age population is forecast to surpass China’s). As a result, Africa is expected to experience a dramatic decline in its dependency ratio—the number of children and the elderly supported by each worker. This development will contribute to continued increases in GDP per capita in the next decades and comes at a time when dependency ratios in virtually every other region of the world are increasing, with negative implications for GDP growth in those areas.

A Youthful Market

Africa also has the world’s youngest population—more than half its inhabitants are under 20 years old, compared with only 28 percent in China. Among the residents we surveyed in urban centers, we found that the 16-to-34 age group already accounts for 53 percent of income. And the consumption habits of youth are quite different from those of their elders; younger people in Africa, for example, are more likely to search for information online (67 percent of 16-to-24-year-olds are online, compared with 32 percent of the 45-and-older group) and to seek products and stores that reflect the “right image.” They are also more

educated, with 40 percent having completed high school, compared with only 27 percent of the 45-and-older group. These qualities point to a major change in consumption habits as this cohort ages, its incomes increase, and its behaviors and decision criteria become the societal norm.

An Emerging, Optimistic Consuming Class

By 2020, more than half of African households are projected to have discretionary income, rising from 85 million households today to almost 130 million in 2020. Africans share the optimism of that economic forecast: 84 percent of those surveyed said they expect their households to be better off in two years (Exhibit 2). Sub-Saharan Africans are the most optimistic—97 percent of Ghanaians, for example, said they will be much better off in two years. Overall, consumers are increasing spending across most categories.

Healthy Urbanization

With 40 percent of its population living in cities, Africa is more urbanized than India (30 percent) and nearly as urbanized as China (45 percent). By 2016, over 500 million Africans will live in urban centers, and the number of cities with more than 1 million people is expected to reach 65,

compared with 52 in 2011.This is already on par with Europe and higher than India and North America.

All the above have implications for consumption habits. Africa’s consumer-facing industries are expected to grow by more than $400 billion by 2020

A Modernizing Retail Trade Structure

There are signs that the formalization of retail will dramatically increase in coming years. Experience from around the world shows that retailing starts to expand when a country’s GDP per capita reaches $750 and really takes off at a GDP per capita of $3,000. Our research suggests that organized trade typically grows tenfold over this period of growth in GDP per capita. This is beginning to play out in some African countries: Shoprite is operating in 16 countries, Massmart in 14 countries, and Woolworths in 11 countries. In Nigeria alone, international-store openings are growing by 36 percent a year, albeit from a low base.

The continent is actually a very hopeful one. Understand her.

References

D. S., & Majeski, S. (2009). U. S. Foreign Policy in Perspective : Clients, Enemies and Empire (1 ed.). Routledge.

Lee, P. (2001). Documents Expose US Role in Overthrow of Nkrumah. Africa Dialogue Series, No. 197: Nkrumah and the CIA IV. University of Texas (Austin). Retrieved August 27, 2013, from University of Texas, Austin: https://www.utexas.edu/conferences/africa/ads/197.html

Gebe, B. Y. (2008, March 15). Ghana’s Foreign Policy at Independence and Implications for the 1966, Retrieved August 27, 2003, from http://www.jpanafrican.com/docs/vol2no3/GhanasForeignPolicyAtIndependenceAnd.pdf

[1] https://edition.cnn.com/2016/08/18/africa/real-size-of-africa/index.html

[2] https://www.britannica.com/topic/colonialism/European-expansion-since-1763

[3] http://foreignpolicy.com/2017/06/20/64-years-later-cia-finally-releases-details-of-iranian-coup-iran-tehran-oil/

[4] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1953_Iranian_coup_d%27%C3%A9tat

[5] https://thisisafrica.me/world-scams-africa-unbalanced-reality-aid-africa/

[6] http://www.gfintegrity.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/GFI-IFF-Report-2017_final.pdf

[7] GFI: Illicit financial flows (IFFs) are illegal movements of money or capital from one country to another. GFI classifies this movement as an illicit flow when the funds are illegally earned, transferred, and/or utilized.

[8] https://www.uneca.org/pages/statement-mr-carlos-lopes-un-under-secretary-general-and-executive-secretary-eca